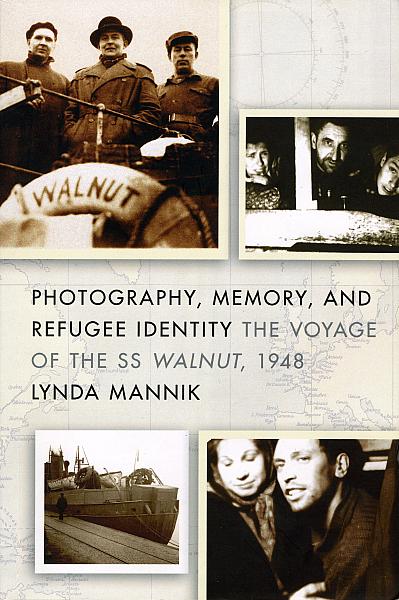

Lynda Männik. Photography, Memory, and Refugee Identity: the Voyage of the SS Walnut. UBC Press, Vancouver, Toronto, 2013.

Visitors to the Pier 21 Museum in Halifax encounter almost at the outset of their visit a display dedicated to the SS Walnut, a former British minesweeper that arrived there on December 13, 1948, carrying 347 Estonian refugees. This in a small ship originally meant to sleep 18 crewmembers. The Walnut and those on board made history, forcing Canadian authorities to change refugee rules as pertains to legal immigration and entry into the country.

The ship had been purchased outright in Sweden, and those on board were legally stateless, as Estonia was under Soviet occupation and their previous citizenship in Estonia was no longer internationally recognized. The fear of being returned to Soviet occupied Estonia by Swedish authorities was great, prompting many to undertake a perilous and long sea journey. Canadian officials were at a loss when it came to these 347 brave souls. They owned the ship, could not be returned to their country of origin, as was done regularly with stowaways and others hoping to create a new life in the land of the Maple Leaf. Media attention, notably in The Toronto Star and The Globe and Mail forced immigration officials to accept the Estonians, thus also creating a precedent for future refugee claimants.

The Pier 21 display has now been most excellently been complemented by anthropologist Lynda Männik’s, a daughter of one of the passengers, book on the experience and its ramifications. This is a dense and superbly researched works, centering not only on photographs taken at the time, meant initially for personal memories, as well as interviews with surviving passengers, who held a sixtieth reunion in December of 2008, documented in this newspaper by Tiiu Roiser, herself a refugee descendant.

Rich in detail, Männik notes in this splendid book that one of the benefits of the personal photograph collection at Pier 21 is their use as an educational program. Männik writes that these photos “became a tool for gaining the attention of Canadian school children concerning official narratives about multiculturalism and good citizenship practices.” The collective “experience of migration by boat are used to promote critical aspects of Canadian nationalism.”

Advertisement / Reklaam

Advertisement / Reklaam

The author’s critical methodology makes her work stand out as more than just a history. While it is that, certainly, the focus on historical collections of images creates an ethnographic study that keeps the reader enthralled. The dense text is not a fast read, adding to the work’s value by keeping the reader involved. As an anthropologist Männik’s approach is distinct from that of the historian; however, the two methodologies are - due the fact that there remain many with memories of the ocean crossing - necessarily entwined.And although much is made of how these memories and the refugee identity had a tremendous impact on Canadian immigration policy, this book remains above all a focus on Estonians. As Männik notes, the Walnut collection at Pier 21 “allows for the representation of individual experience and the reimagination of various collective identities through a publicly performed past that continually reinvents ideas about refugees.”

The photographs and the recollections of those who arrived in Halifax in 1948 are part of the tools in the author’s toolbox, but chief among those implements utilized is Männik’s ability to not only recreate the journey and the memories of the crossing, complimented by a very lucid, focused style of writing.

Photographs and memory operate, as she notes, in conjunction with identity that cannot be confined to a specific geographic space or time. Photographs also pack an emotional wallop when returned to decades after an experience. Memory, on the other hand, as Männik emphasizes is part of the crucible of forging a national identity, being at the “heart of nationalist struggles.” For the 347 on board the [/i] Walnut[/i] the desire to get as far from the claws of the Soviets as possible united them in a way that few experiences could have.

While a visit to the Pier 21 Museum is highly recommended a very viable and enthralling alternative is reading this book. Certainly, as the daughter of one of those on board the ship, Männik has a very personal connection with the refugee identity. However, she never lets this interfere in what is an excellent scholarly work, sure to not only capture Estonian-Canadian readership, but all those interested not only in escape narratives but engaging insights into the experience of arriving in a new country.

Advertisement / Reklaam

Advertisement / Reklaam

The footnotes, extensive bibliography, as well as the obvious - numerous photographs - all add to the rich tapestry found on these pages. It is well worth the effort to find and read this work, for any reader will be greatly enriched by the experience.TÕNU NAELAPEA